Philosopher Eugene Thacker has been playfully described as a person who writes books for nobody. This, of course, is not true because I maintain that his seminal work, In the Dust of this Planet, was written for anyone who finds themselves in awe (or terrified) of the subliminal unknown. I dusted the old copy from my overflowing shelf of vanity books – you know, those someday books we designate to an isolated corner and tell ourselves we will get around to reading when the world collapses again. As if it hasn’t already. It seemed like a fitting supplementary read while primarily referencing Philosophical Approaches to Demonology in my Philosophy of Religions course this past fañomnåkan. Was this a sure sign of imminent doom?

Outside of the limitations of one semester, Thacker takes us through historical emergences of the demon. He writes, “If the demon is taken in this anthropological sense as the relation of the human to the non-human (however this non-human is understood), then we can see how the demon historically passes through various phases: there is the classical demon, which is elemental, and at once a help and a hindrance (“the demon beside me…”); there is the Medieval demon, a supernatural and intermediary being that is a tempter (“demons surround me…”); a modern demon, rendered both natural and scientific through psychoanalysis, and internalized within the machinations of the unconscious (“I am a demon to my- self…”); and finally a contemporary demon, in which the social and political aspects of antagonism are variously attributed to the Other in relationships of enmity (“demons are other people”) (Thacker, p.41-42). Thacker maps demons in relation to the human. I question whether the issue with the Other is not the demon per se, but that the Other is always ever viewed through a lens of the self.

Throughout our course, we had the opportunity to examine such demons in text and through film. There’s Socrates’ daemon beside as moral conscience and compass. Demons surrounding as a result of religious othering: Christianity’s Lilith, Islam’s Djinn, the Hasidic Mazzik, and Buddhism’s Mara. The nihilistic self-demon of existential paralysis, and other people demons which emerge from modern socio-politico totalizing relations. We ventured through a humanistic understanding of the demon into the pantheistic gnostic tradition of a demon as a united entity, while briefly glazing over indigenous traditions with an inconclusive understanding of the demon as sort of instability, a disharmony within the ebbs and flows of nature’s interconnected force. Thacker suggests, “Perhaps there is a meaning of the demonic that has little to do with the human at all – and this indifference is what constitutes its demonic character. If the anthropological demon (the human relating to itself) functioned via metaphor, and if the mythological demon (the human relating to the non-human) functioned via allegory, then perhaps there is a third demon, which is more ontological, or really ‘meontological’ (having to do with non-being rather than being)” (Thacker, p.50). Such is a demon that is unknown to us. For Thacker, the confrontation of this demon leaves one in crippling awe, morbid dread, and on a good day, pessimistic despair. The limits of our knowledge cannot settle this infinitely unknowable demon into a static, fixed, nor graspable being.

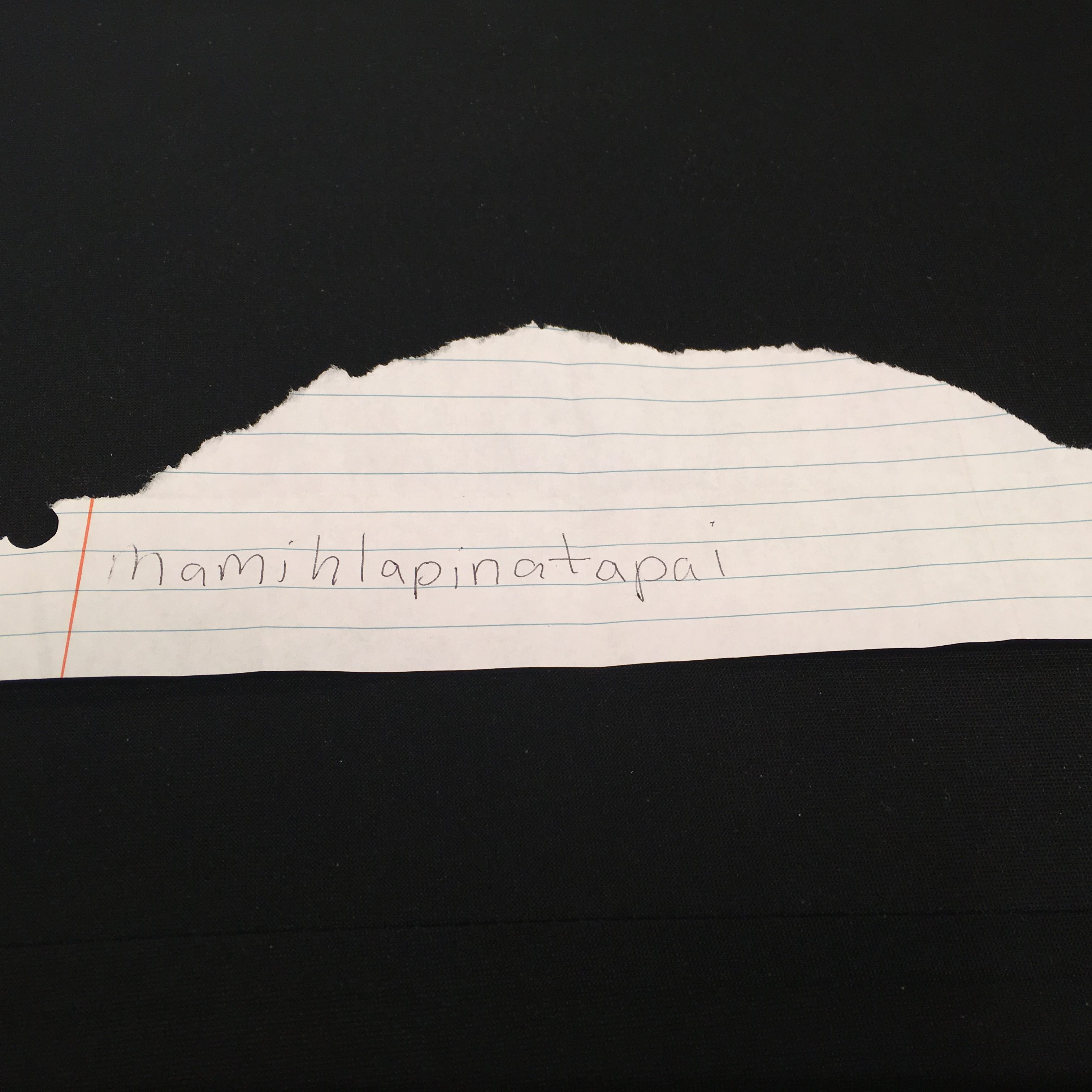

For my creative project, I aimed to confront this unsettled demon by exploring beyond a humanistic, naturalistic, and even a pantheistic interpretation. Enter the cyborg. The cyborg, much like the demon, according to Donna Haraway in A Cyborg Manifesto, is a way of thinking about the increasingly blurred boundaries between humans and the unknown. In stark contrast to Thacker’s cosmic horror, however, Haraway offers us a situated optimism. The cyborg is a hybrid of flesh becoming-with machine. This entity challenges our preconceived notions of what it means to be a human, inviting us to imagine new forms of relating between the tangible and the unknown. If we can effectively move from Thacker’s dark ontology into the realm of Haraway’s ethics and ecology, in a sense, could we embrace this new demon in its continual state of becoming? Granted, cosmic pessimism allows for the rejection of any teleological aim, situated optimism picks up where it may fall short by affirming meaning-making in the process – I engage with what is outside of me, what is unknown to me, not in attempt to capture it, but to move, create, and play in tandem. I would encourage us to embrace this hybridity. To encounter the demon not as a veritable threat, but as a continual process of Nietzschean reinterpretation and revaluation.

The process of creation is a symbol of liberation. Creation through difference rejects absolute categories and oppressive binaries that have restricted our understanding to origin stories of morality and power for too long. Reflecting on the dominant binaries that have been prescribed throughout history: good vs. evil, angel vs. demon, male vs. female, self vs. other, nature vs. machine – my demon disrupts these binaries, showing us that reality is far more fluid and complex. Both organic and technological, they embrace ambiguous multiplicity, relational opacity (Glissant, 1997), inviting us to engage with the unknown’s indifference through a poetics of embodied imagination.